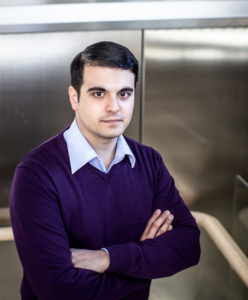

WORLD. According to many studies, the 2010s was the most prosperous decade in global history. Globalisation, often defined as higher levels of economic and technological flows, has despite its problems resulted in rapid advancement of human progress. Levels of extreme poverty, illiteracy and mortality have all been reduced greatly. Despite backlashes often labelled as ‘Brexit and Trump’ there are many reasons to remain optimistic and advocate for a brighter future. This is one of the messages by American Enterprise affiliated scholar Dalibor Rohac in his recent book ‘In Defense of Globalism’.

Dalibor Rohac

Rowman & Littlefield

As a moderate intellectual Dalibor Rohac gives an important contribution to contemporary debate filled with higher degree of polarisation and political tribalism where the term globalism often is regarded as synonymous with elitism and technocracy. The author presents several vital points on how globalism, mainly as an idea based on the importance of international institutions and polycentric governance, benefits people across the world regardless of their social status. One can describe the book as ‘Globalism for dummies’, providing basic information about the meaning and history of governance models above the sovereign state levels.

As a moderate intellectual Dalibor Rohac gives an important contribution to contemporary debate filled with higher degree of polarisation and political tribalism where the term globalism often is regarded as synonymous with elitism and technocracy. The author presents several vital points on how globalism, mainly as an idea based on the importance of international institutions and polycentric governance, benefits people across the world regardless of their social status. One can describe the book as ‘Globalism for dummies’, providing basic information about the meaning and history of governance models above the sovereign state levels.

One of the main points in the book is that ideas of international, supranational and global institutional setups are deeply rooted in the development of free and democratic societies. Therefore, it is evident among other reasons why EU countries as Sweden and Germany or American states as California and Texas are among the most globalised parts of the planet. Dealing with global problems and challenges demands the common institutions. Rohac argues that the current nationalist and populist movements are doomed to fail because of their inability to provide meaningful answers to problems connected to climate change, economy and migration.

The book is written for a wider public, but it focuses its messages particularly to actors on the political right, i.e. conservatives, liberals and libertarians. In recent years, many former right-wing supporters of globalisation have transformed into anti-globalists and ‘sovereigntists’. A development manifested in the rise of nationalist conservatives and right-wing collectivists, and the emergence of protectionists policies in the USA.

In addition to ideological support for globalism, the book also provides vital arguments in favour of European patriotism as opposed to state-centric and nationalist ideas regarding governance, democracy and identification.

According to Rohac, shared institutions like those in Europe are vital to secure the market economy, individual freedom and the rule of law. Throughout his book, Rohac encourages both historical reflections, such as references to the Hanseatic League and Holy Roman Empire, as well as future-oriented rethinking by emphasising several critical points when it comes to pooling sovereignty and shaping mandates of international institutions. As Rohac points out, in order to maintain social trust and legitimacy, the institutions which are above the national level must be more limited and focused on their scope. The risk is otherwise that social trust will deteriorate, as in the case of the International Monetary Fund which today undertakes tasks which it was not initially intended to perform.

Rohac offers a middle way between those ideas and actors who believe in the myth of ‘free sovereign nations’ and those who believe in utopias of a unitary world government. Before reading the book, I was expecting a chapter offering new and radical solutions with more detailed proposals for institutional development at a global level, such as the creation of a worldwide police force or a climate ministry. No such ideas are to be found, but the author is clear and maintains his agenda on providing support for the current institutional frameworks and points out what must be changed, improved and reformed.

The book’s most powerful message is that the nation-state is not the final point of social development. Therefore, the continuous institutional diversity from local to global level is a key to a brighter future and prosperity for our human civilisation.

vladan.lausevic@opulens.se