POETRY. Sean Bonney’s poems do, in the end, express a great belief in poetry. In one poem, Bonney contemplates ‘loneliness’, an effect that grows in power to encompass ‘Syria’ and ‘Templehof’, an effect that ‘destroys private property’, says Johannes Göransson in this essay.

1.

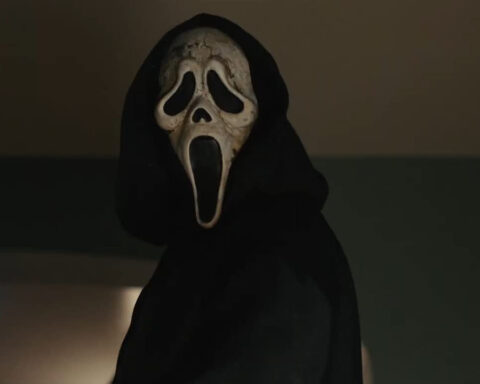

The scream. It’s a motif I keep coming back to when reading UK poet Sean Bonney’s brilliant final collection, Our Death. Throughout the book, a scream pierces the text, the city, the capitalism. This might seem paradoxical because the book is not very shouty. It’s often reflective, pared-down – austere, even. Yet it keeps coming back to the act of the scream: ‘I think of my friends as blackbirds/screeching from rooftops/murdered by rising rents.’ Or: ‘My coffee cups and typewriter I leave to, I dunno, whoever can scream the loudest.’ Or, more importantly: ‘I take that scream to contain all that is meaningful in the word communism.’ Or perhaps most hauntingly, when he recollects an early dream – probably his first – about a quarry where there’s a mouth in the wall, and that mouth begins to ‘make a low moan’, a moan which continues to build in intensity until it becomes ‘a siren’s shriek’.

This scream makes me think of a classic quote from 20-century modernism: Theodor Adorno’s assertion that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’. Our Death is a ‘barbaric’ collection of poetry. To begin with, it constantly interrupts itself with vulgarity and violence, as if both to literalise the violence of capitalism and to destroy the beauty of the poems. We repeatedly get lines like ‘I boot your face in over and over’ and ‘pack up your roses, asshole, get out’. Swedish readers may think of Johan Jönson’s 1000-page opuses to the obscenity of having a body in late capitalism.

Like Jönson, Bonney’s poems do, in the end, express a great belief in poetry. In one poem, Bonney contemplates ‘loneliness’, an effect that grows in power to encompass ‘Syria’ and ‘Templehof’, an effect that ‘destroys private property’. And in the end, it too ‘is screaming is smashing your windows with boots and chains/its ruined hands’ loneliness a sharpened axe.’ The book seems to stage a struggle for the very existence of poetry. In essence, it becomes violence, a scream, to overthrow. But then it becomes poetry again. There is a sense of a tug of war between violence and poetry. Poetry is a loneliness, but it is also a scream, communism and an almost messianic violence.

But the scream is barbaric in another, more specific sense: barbaric originally means foreign. And the scream in Bonney’s book has much to do with the sense of a foreign language. Over and over, Bonney’s speaker contemplates foreign sounds in his mouth: ‘A kind of high metallic screech. Unpronounceable. Inaudible.’ Or:

“For lack of anything better to do, I sit here and try to conjure up some kind of meaning from the scars that have been left there. I sit there in the dark and read your poetry. Or rather, I reconstruct from memory what translations of it exist. I stare at the traces of an alphabet I don’t understand. I think that in the gulf that separates your poetry from mine I might be able to find the beginnings of a counterlight to see by, or a way of pronouncing the language needed to help undermine the fascist tinnitus that all of our sensory networks have become.”

In this poem, addressed to Greek poet Katerina Gogou becomes a ‘scream’ not so much in loudness but in its foreignness, a foreignness that is also equated with a ‘scar.’ He takes a foreign, ‘unpronounceable’ entity into his mouth. And that is the scream of poetry. Almost a reverse scream, reverse exclamation, a language that goes back in the mouth, becomes unpronounceable.

4.

I am here reminded of a very different writer, Anne Carson. In her essay ‘Cassandra Float Can’, Carson discusses the art of ‘prophecy’ as an art that creates a ‘rip in spacetime’. ‘What is it like to be a prophet?’ Carson asks. ‘Everywhere Cassandra ran she found she was already there.’

Bonney the prophet: throughout Our Death, wherever he goes, he’s already there.

5.

For Carson, the art of prophecy is inextricably bound up with translation: ‘Whenever I am engaged on a translation project, I experience continually, offside my vision, a sensation of veils flying up.’ This translation-ness is connected in Carson’s mind to Cassandra whose opening line is ‘OTOTOTOI POPOI DA!’ Carson explains: ‘This utterance is a scream. It is untranslatable, yet not meaningless. A scream conveys a specific emotion and can make things happen.’ The way it is connected to translation is this: ‘What is Cassandra doing speaking Greek? She is, after all, a Trojan princess who has never been away from home before.’ The answer Carson gives is this:

‘Aeschylus would like us to see the veils flying up in Cassandra’s mind, would like us to be wondering at what level of herself she is translating some pure gash of Trojan emotion into a metrically perfect line of Greek tragic verse and what that translation has to do with the arts of prophecy. Because in both cases, there is some action of cutting through surfaces to a site that has no business being underneath. What is the future doing underneath the past?’

Bonney’s book is an act of prophecy. In essence, it’s a translation (of Gogou, Anita Berber, Pier Paulo Pasolini, etc.) and it’s an act of ‘cutting through surfaces’. The scream – the vulgarity, the obscenity, the poetry – is about cutting through surfaces.

Q: What does he find beneath the surfaces?

A: ‘The secret workings of the sun’; ‘revenge’; and, most importantly, what Bonney in an essay calls ‘the language of the dead’.

7.

This language of the dead – ‘our death’ – is stunning, veering as it does between the surreal and the stark, the poetic and the obscene, beautiful and depressing:

‘Fuck it. The sun is doing whatever suns do

The citizenry all creeping like flowers.

Idiots. The sky is grey on further grey and

The haunting, its sharpened hail, never stops.’

8.

In the same essay I mentioned above, Bonney gives us a succinct answer to what it is he aims for his poetry to do, distinguishing it both from the establishment ‘accessible’ poetry on the one hand as well as the experimental establishment poetry of conceptualism:

‘Poetry doesn’t talk about the world, nor does it create meaning, but instead aims at meanings not yet articulated, meanings not catered to in the currently available aesthetic and social networks. This pushes poetry to a critical edge-condition which risks its destruction as poetry in a way that is far more serious than any silly corporate nihilism claiming to have “killed” “poetry”. Meanings are communicated, which risks tearing the poem apart.’

The prophecy scream is the poem coming apart. Language coming apart. In Our Death, Bonney writes: ‘I kept screaming, past all voice, all body, all of my borders.’

9.

There’s another vein in the book – related the issue of the scream and prophecy – and that’s the body. Here I think of another classic modernist statement, André Breton (in Nadja): ‘Beauty will be convulsive, or it will not be at all.’ The body in these poems is constantly flawed, damaged, high, tired, falling apart, spastic: ‘The catastrophe that is his body.’ It is as if the body registers all the violence of capitalism in a direct way. Like Raul Zurita, who registered the violence of the Pinochet coup by scarring himself, by burning his face, by screaming, Bonney takes on the violence with his body to cut through, to make visible these forces. When this book talks about ideology, it is visible: cops enact violence. The poets fight back. The violence has been laid bare.

10.

It’s hard for me to write about screams and not think of two screams from my own life. When my third daughter was born, she didn’t scream. Couldn’t scream. I could see her little face, and she was trying to scream, but nothing came out. The doctors rushed her to some other room and came back with a grim prognosis: due to a hole in her diaphragm Arachne could not breathe. When she heard this news, my wife Joyelle let out a scream like I have never heard before; it knocked me over. I fell on the floor and could not get up. The scream had torn the veils off for me. I was trying to make sense of my experience, I tried to spin it, tried to make it all right, but the scream meant I couldn’t. There was no way to make this OK. This may seem like a very private experience, but the reason for Arachne’s congenital disability was, of course, environmental. The earth had translated its toxicity into Arachne’s body. And the scream (I mean the screams) was the unpronounceable, barbaric poetry of a world setting itself on fire.

info@opulens.se