LIFE. On October, Saturday 22nd, 1938, a 46-year-old woman wanders in Buenos Aires towards the train station; she buys a one-way ticket to Mar del Plata. She moved to a modest boarding house, having the blurry fate of committing suicide. It is said – the incident is obscure- that she is sick, tired and longs for death to set her free. Perhaps her time goes by in an old bench thinking about her life. Maybe She spends time writing her poem “I’m going to sleep too”.

I’m going to sleep, my nurse, tuck me in. Put a flashlight on the headboard; a constellation, the one that you like they are all good; dim it a little. She goes to the post office and sends the poem to “La Nación” newspaper. She stays awake the whole Monday night because of her moral confusion. Probably screams of rebelliousness and words of submission were heard. She talks to herself. She writes a letter to the only son she had, Alejandro, 26 years old.

She goes out and heads to the sea at 1:00 am. Her biographers assured she jumped into the sea from a breakwater. The myth, however, more poetic and with more spirituality, was that she slowly walked into the water.

Hours later, two young workers who were strolling down La Perla beach found her body. She was Alfonsina Storni, one of the most important poets of the century. Alfonsina Storni was immortalised in the song “Alfonsina y el mar” (Alfonsina and The Sea) by Luna and Ramírez.

Through the soft sand that the sea laps against

Your little footprint will not ever come back

A path full of pain and suffering

Reaches the deep water

A path only of silent grief Reaches the surf.

Alfonsina Storni was a Gemini of 1892. Fire Dragon. She once said: “I was called Alfonsina, which means willing to anything”. She was born in a canton of Switzerland. Her family settled in San Juan, later on, in 1901, they moved to Rosario. When Alfonsina was 10 years old the “Café Suizo” is her family business, where the girl works as a dishwasher and waits the tables. Her father, depressed and alcoholic dies in 1906. Alfonsina, who does not stop writing poems, works as a cook and as a labourer in a workshop of caps. She dedicated some time to the theatre too. She finally graduated as a teacher.

They were seen together. The photographs show them happy. Her friend Nora Lange says that she witnessed an erotic game for children: Quiroga holds in the air a chain clock they both had to kiss in the opposite faces; in the right moment Quiroga raised the clock. Naughty boy.

At age 19, She already writes, recites and publishes in magazines. And then came love. It is said that in a literary soiree in Santa Fe, Alfonsina had an affair and from the affair, she had a son, Alejandro, in 1912. From birth, another verse appeared: I am like a she-wolf, I walk alone, and I laugh…the son and then I, and then…whatever! In spite of the years Alejandro´s father name remains unknown, he was a journalist, older, and married.

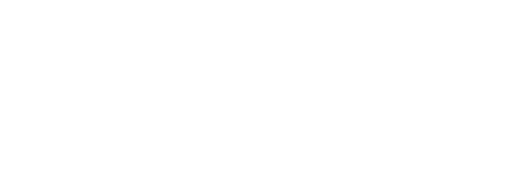

Alfonsina, a single mother and a feminist, moves to Buenos Aires. In 1920, she wins the First Municipal Prize of Poetry and the Second National Prize of Literature for “Languidness”. In 1925, “Ochre” is published, In 1926 “Poems of Love”, 1934 “Seven Wells World” and in 1938 ” Mask and Shamrock”, which is the last book. Alfonsina Storni, brave speaker for women’s rights and a driving force of the Writers Society of Argentina, she had many friends. She asked Leopoldo Lugones if he could read some of her verses in 1915: She wrote; ” This I am asking you for a reason, it is because my book is due to be published soon. I know that I am going to be labelled as an immoral”.

In 1919 Amado Nervo arrives in Argentina as an ambassador for his country and goes to the same meetings Alfonsina does. She dedicates him a copy of “The Uneasiness of the Rosebush “. In the dedication, she called him “Divine Poet”. To Juana de Ibarbourou, whom she met in Montevideo in 1920, she seemed happy, perky, sometimes acute, and sarcastic.

She met Horacio Quiroga, a story writer, in 1922. She liked Quiroga. Obviously. He was a mixture of insolent and a tragic beast, a real magnet for women. His biographers say that he was a womaniser. Smear? Read this letter of Quiroga: “There is a girl in Buenos Aires, an admirable 16-year-old creature, to whom I recall well since I once dinned at her place, spending the long hour looking for with my foot what, oh, Lord! I had agreed to find, with someone else’s acquiescence. I even put my hand under the table to arrange my napkin, and put it right in her knee for a moment, just for a moment”.

They were seen together. The photographs show them happy. Her friend Nora Lange says that she witnessed an erotic game for children: Quiroga holds in the air a chain clock they both had to kiss in the opposite faces; in the right moment Quiroga raised the clock. Naughty boy.

One day the Chilean Gabriela Mistral called her on the phone. She wanted to meet her. When Gabriela saw her she was surprised: “The head is extraordinary, not for cheated features but for her silver hair, which frames a 25-year-old visage”. The Vicuna poetess insists “I have not seen a hair more beautiful than that, it is strange like moonlight at noon would be. It was golden, and some sweetness remained in the white clusters. The blue eyes, the retroussé nose, very funny and the rose skin, give her a child thing which challenges the astute conversation and mature woman”.

She met Federico García Lorca in the famous café Tortoni when he went to Buenos Aires to direct his play “Wedding of Blood”, between 1933 and 1934. She dedicated him a poem, “Portrait of García Lorca”: In comes a Greek / because of his distant eyes (…). Out goes his throat/outside/ asking / for the moon knife / sharpen water (…) Let the head fly, / the head alone / wounded by sea waves / black ones…”.

In the summer of 1935, she knew the terrible news: she had breast cancer. She was operated on, but the cancer continued. She suffered from depressions. Since then she called the sea in her poems and talks about the embrace of the sea and the crystal house waiting for her there in the bottom, in the Madre pore avenue. The suicide floats in the environment. In 1937, Horacio Quiroga also gets sick of cancer. One midnight he took cyanide. Alfonsina Storni said good-bye with moving verses: “Dying like you, Horacio, in your full senses, like in your stories, It is not bad”. Then Leopoldo Lugones poisoned himself.

Storni, Dragon of fire, he begged the sea, his rage, his fierceness:

Oh sea, give me your tremendous rage,

I spent a life forgiving

Cause I understood, sea, I gave myself away:

“Mercy, mercy for the most offensive”.

Give me your salt, your iodine, your fierceness,

Sea Breeze! Oh, tempest, oh anger!

Poor me, I am a sharp rock,

And I die, sea, I succumb in poverty

Finally, the sea asked for her. And, in the place where she went down ready for everything, a Monday night, there is a statue in her honour, overlooking the sea.

info@opulens.se